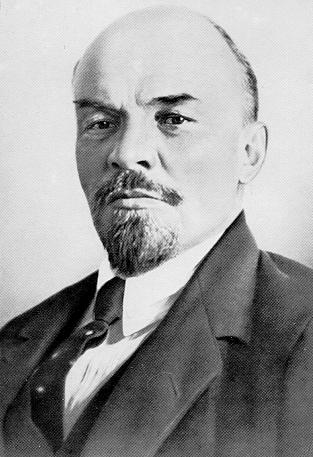

Lenin, Vladimir Ilich (1870-1924), Russian revolutionary and political theoretician, who was the creator of the Soviet Union and headed its first government.

Lenin, originally named Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov, was born in Simbirsk on April 22, 1870, the son of a successful government official. The first breach in Lenin's comfortable childhood came in 1887, when the police arrested and hanged his elder brother for plotting to assassinate Tsar Alexander III. Later that year Lenin enrolled in the Kazan' University (now Kazan' State University), but he was quickly expelled as a radical troublemaker and exiled to his grandfather's estate in the village of Kokushkino.

During this first exile (1887-1888) Lenin became acquainted with the classics of European revolutionary thought, notably Karl Marx's Das Kapital, and he soon considered himself a Marxist. Finally granted the necessary permission, he passed his law examinations in 1891, was admitted to the bar, and worked as a lawyer for the poor in the Volga town of Samara before moving to St Petersburg in 1893.

Organizer

In St Petersburg, Lenin joined the growing Marxist circle, and in 1895 he helped create the St Petersburg Union for the Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class. Police soon arrested the leaders of this organization. After 15 months in jail, along with another union member, Nadezhda Krupskaya—soon to become his wife—Lenin went into Siberian exile until 1900. At the end of his first period in Siberia Lenin went abroad, where he joined Georgy Plekhanov, L. Martov, and other Marxists in creating a newspaper, Iskra (The Spark). The paper proved to be an effective device in uniting the existing Social-Democrats and inspiring new recruits. In exile Lenin wrote his masterpiece of organizational theory, What Is to Be Done? (1902). His plans for revolution centred on a highly disciplined party of professional revolutionaries, who would serve as the "vanguard of the proletariat" and lead the working masses to an inevitable victory over tsarist absolutism.

Lenin's insistence on the centrality of professional revolutionaries caused a split within the Russian Social Democratic Labour party; at its second congress (1903) it broke apart. Lenin's faction emerged with a small majority of the congress, hence the name Bolshevik (from the Russian word for majority); the opposition became known as Mensheviks (from the Russian word for minority). Quarrels between the two factions dominated party politics until World War I.

Exile

Lenin spent most of the years until 1917 in exile in Europe. He returned to Russia after the peak of the 1905 Revolution, but the reaction that descended on the country in 1907 again forced him to flee abroad.

As he wandered through Europe, Lenin lived a hard, bitter existence. He exchanged recriminations with the Mensheviks about the Revolution's failure, and many of his most talented disciples deserted him. At this time he wrote his major philosophical tract, Materialism and Empirio- Criticism (1909). Three years later, at a party conference in Prague, the break between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks became final.

When World War I broke out in 1914, Lenin opposed it on the grounds that workers were fighting each other for the benefit of the bourgeoisie. Instead, he urged socialists "to transform the imperialist war into a civil war". He expounded and systematized Marxist views of the war in Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916), arguing that only a revolution that destroyed capitalism could bring lasting peace.

Revolutionary Leader

The Revolution of March 1917 that overthrew the tsarist regime caught Lenin by surprise, but he managed to secure passage through Germany in a sealed train. His dramatic arrival in Petrograd (as St Petersburg had been renamed) occurred one month after rebellious workers and soldiers had toppled the tsar. The Petrograd Bolsheviks, including Joseph Stalin, had agreed with the deference the Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies showed the bourgeois provisional government. Lenin immediately repudiated this line of policy. In his "April Theses" he argued that only the Soviet could respond to the hopes, aspirations, and needs of Russia's workers and peasants. Under the slogan "All Power to the Soviets", the Bolshevik party conference accepted Lenin's programme.

After an abortive workers' uprising in July, Lenin spent August and September 1917 in Finland, hiding from the provisional government. There, he formulated his concepts of a socialist government in a famous pamphlet, State and Revolution, his most important contribution to Marxist political theory. He also bombarded the party's Central Committee with demands for an armed uprising in the capital. His plan was finally accepted; it was put into effect on November 7.

Premises

A few days after the November Revolution, Lenin was elected chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, that is, head of government. He acted pragmatically to consolidate the power of the new Soviet state. At his urging, private enterprise, except for such institutions as banks, was not nationalized. He charted a slow course towards socialism and avoided the opprobrium attached to one-party rule by including the Left-Socialist Revolutionary party in his government. His overriding concern was the preservation of the Revolution and Soviet power against enemies both abroad and at home. In line with these practical considerations Lenin accepted the onerous German terms for the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty. His tenacious struggle to maintain power, however, cost the young Soviet regime dearly in the 1918-1921 civil war. Together with Leon Trotsky, the genius behind the Red Army, he set the course that brought the Soviet Union victoriously through the civil war.

After the war Lenin issued the New Economic Policy, returning the Soviet Union to the market economy and pluralistic society of early Soviet rule. At the same time, however, he called for a ban on factionalism and insisted on the principle of one-party rule.

The first of three strokes incapacitated Lenin in May 1922. He recovered somewhat, but never again assumed an active role in the government or the party. After a partial recovery in late 1922, he suffered a second stroke in March 1923, which robbed him of speech and effectively ended his political career. Lenin died in the village of Gorkiy, just outside of Moscow, on January 21, 1924.

Although not an extraordinary philosopher, Lenin was a brilliant revolutionary thinker and strategist, whose clear-sighted realism guided the Bolsheviks to seize and maintain power. He did not formulate any one solution to the dilemma of how to build a workers' state in a peasant society. His interpreters and critics differ. Some see a continuity between Lenin's early ideas and those of Stalin, while others stress the pluralistic New Economic Policy that he advocated in the last years of his life. Most observers agree, however, that Lenin was the foremost revolutionary figure of 20th-century Europe.